Policy for Campaigns 08: What is a policy cycle?

Where does policy sit in the traditional campaign cycle?

You may be familiar with the idea of a campaigning cycle, which is a tool or schema that provides a helpful process to guide campaigning. In this article, I want to consider where policy fits into this, and whether it makes sense to think of a ‘policy cycle’ as well.

Given that policy is an input to campaigning, I won’t argue that a policy cycle should be a separate thing, or that a policy function should own or run a campaign cycle as a whole. However, I will argue that there are elements of a campaign cycle that are best understood as policy, and should probably be owned or run by a policy team or function. Other parts of the cycle are very clearly the remit of campaigners, but policy should be on-hand with input and support throughout.

We’re talking here about proactive campaigning work, and future articles will look at reactive and day-to-day policy work. However, the distinction is not total and the two can overlap, for instance if your campaign has made progress and as a result there is a formal consultation on something you have been pushing for: your organisation will probably respond to a range of these exercises as a matter of course, but on this occasion you’ll need to consider how to do it in the context of your campaign.

What’s a campaign cycle, and would a policy cycle be useful?

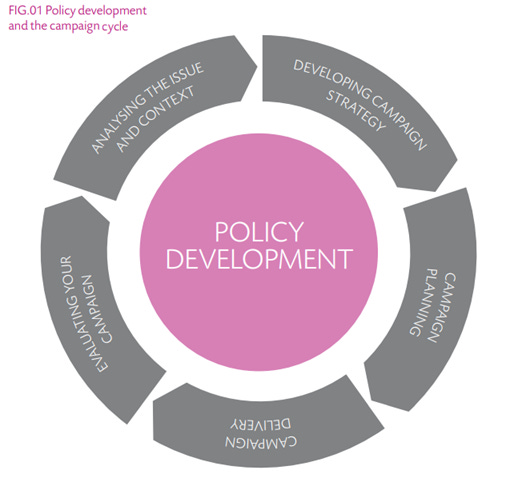

The diagram above is probably the best-known summary of the campaign cycle idea, and I’m certainly a fan of it. It’s a tool: it should stimulate thinking about how to approach the work in question, or at most be a guide; it is not a rigid template. But used appropriately, it can clearly be useful: in particular, presenting campaigning as something that is ongoing and cyclical, requiring regular evaluation and assessment, is crucially important. It’s also helpful in steering the user away from simply rushing headlong into campaigning actions without thinking them through. I suppose what it doesn’t capture is that if an organisation has successfully achieved all the change it needs in order to resolve all its issues, then its campaigning will finally stop. But this is… rare.

I haven’t been able to pin down the origin of the campaign cycle, although it’s certainly been much used by NVCO in its materials for charities. This Skills Third Sector document from 2010 presents it, using the diagram above, and dates its origin to 2005. Do any readers know if it dates back further as a concept?

The same diagram was still in use in 2018, while this Forum for Change document (undated, though the latest external reference it gives is 2009, so certainly after then) includes a version that attempts to incorporate policy.

It was this version that prompted me to think about how policy could most usefully be represented in the cycle. I’m not sure that just plonking it in the middle offers much practical guidance, although there is much more useful material on policy elsewhere in the same document, which the following draws on to an extent.

There’s a risk here of getting very doctrinaire and inflexible about what is policy, what’s “public affairs” and what’s “campaigning”: many organisations will have roles that include elements of two or more of these skills or disciplines, reflecting that the boundaries are not clear-cut. In a small organisation, one person might be doing all the work anyway, while in a very large organisation there could even be entirely separate teams for campaigning and policy. (Structure is another likely topic for future articles.) So the below is not intended to propose a strict compartmentalisation, but hopefully in teasing apart some concepts it will be helpful as a guide to thinking about some of the complexity involved.

Before we go any further though, it’s worth pulling out something that’s implicit in the campaign cycle: there’s an assumption that any organisation using it is in the business of campaigning in the first place. It doesn’t include any element of making reference to an organisation’s strategy or purpose in order to check whether to campaign or not. Given the nature of the tool, that’s fair enough. But it’s worth saying explicitly: for an organisation that exists exclusively to provide its services, whether that’s food, advice, equipment, care, or what-have-you, there shouldn’t be any question of hopping onto the campaign cycle at any point. If an organisation decides it does want to do that when it hasn’t before, it needs a new strategy before it needs a campaign cycle.

Policy in the campaign cycle

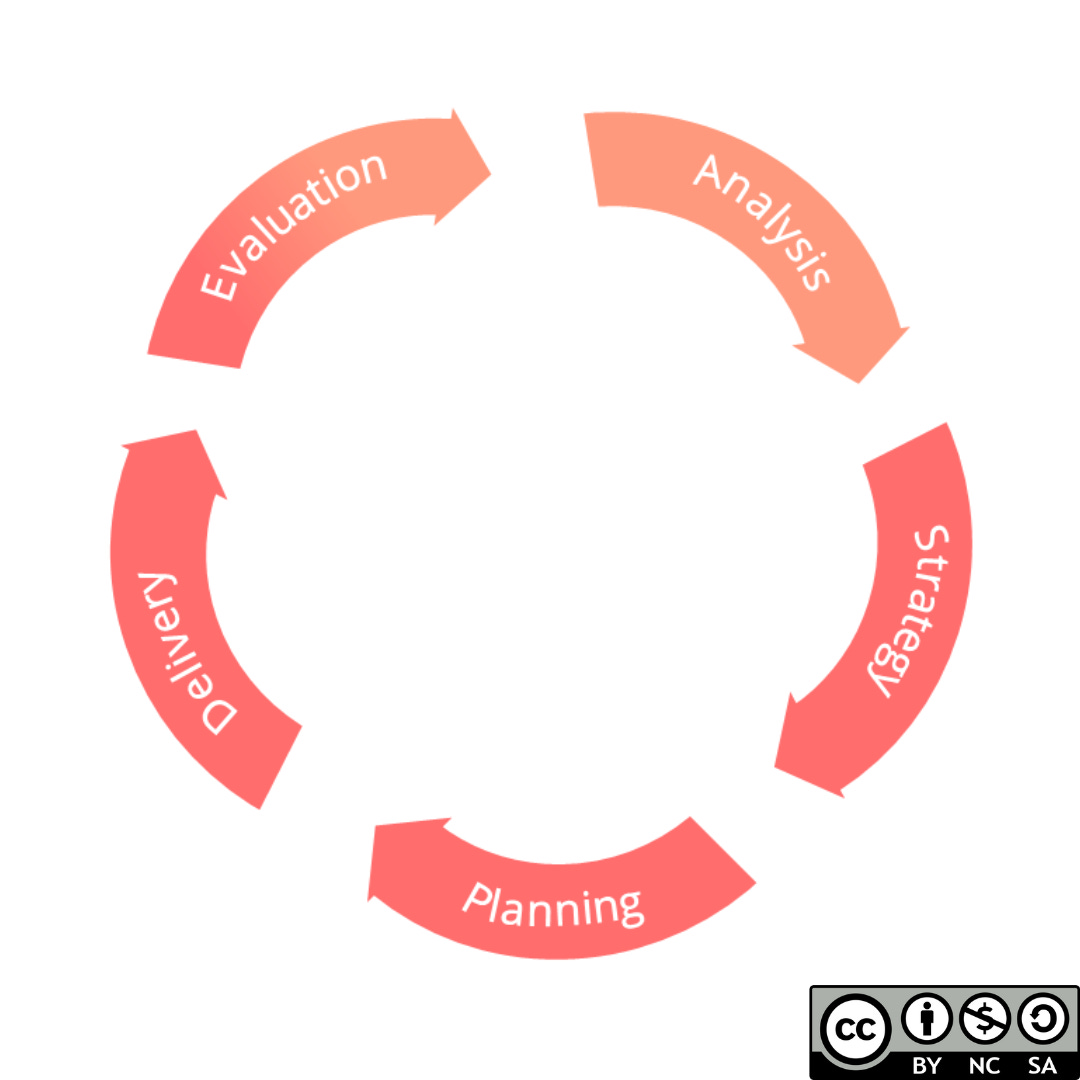

In this version of the diagram, I’ve put the elements that are most clearly policy in orange, and the rest in red. Analysis of an issue must clearly be a policy responsibility, and I’d argue so too should evaluation, mostly. The principal measure of a campaign’s success must be whether it achieved its aims, meaning whether it secured the change it set out to secure. As that change was a matter of policy (see earlier definitions), assessing whether it has happened, and if so with what consequences, must be a matter of policy as well. However, there will be other aspects of the campaign to evaluate, such as how well each element of it worked and what can be done better operationally in future, so there is a broader dimension to that phase, hence the colour gradient on the arrow. Overall though, I’m suggesting that in organisations with clearly delineated roles or functions, those are the two parts of the cycle that policy should “own”.

You could make a case for the “developing strategy” element to be owned by policy as well. At its most basic, a strategy is a framework for making decisions, and can be expressed in the form “we will achieve x by doing y”. Here, the thing you are trying to achieve should certainly be defined by your policy analysis: it is an expression of your policy recommendations or goals. However, the strategy is implicitly a strategy for the campaign: it involves the big decisions about the sort of approach you will take in order to achieve the goals, so in practice I would expect to defer to campaigns or public affairs colleagues at this point.

However, this does illustrate that policy input and support is needed at later stages of the cycle – and indeed, throughout it. We’ll come back to that later.

A policy cycle?

Any tool of this sort will lump a lot of detail together under a few concise headings. In the diagram below I’m not attempting to suggest that the policy side of things is inherently more complex or important, but I am attempting to unpack some of the elements of it and provide some slightly more detailed suggestions. Undoubtedly the more overtly campaign-focused elements of the cycle could be similarly expanded into a larger and more detailed circle by public affairs and campaigns specialists.

The policy cycle has the following suggested elements.

Assessment and evaluation

This will be where the effectiveness of previous campaign measures should be assessed, including learning lessons for future work, and also where the current state of play for an issue should be evaluated. Is there a problem or need to act, whether as a result of an earlier campaign, despite it, or related to its failure? Should something be different? This can include assessment with reference to earlier campaign goals and policy recommendations, but should avoid importing assumptions from previous work. If the answer is that there is no problem, obviously you won’t go through the cycle any further.

Understanding the problem

If you’ve identified that something’s not right and should be addressed, you need to understand it. Identify and review the available evidence, including by getting input from your supporters and others affected. Review relevant work by other organisations in related fields, including what they are doing to address the issue. Also identify areas of uncertainty, where the evidence is weak.

Prioritise the problem

This can easily be missed, and I considered including it in the “understanding” heading above. But there needs to be a point at which you can get out of the cycle if you need to, and you’re more likely to stop a cycle here, rather than by simply concluding there’s no problem at all: if your analysis is that the problem is modest relative to others you’re working on, or that another organisation is doing work that you can’t usefully add to, you may decide to leave things here and halt the process.

Prioritisation should be done with reference to your organisation’s strategy, and with input from your supporters and/or beneficiaries. There may be a governance process to go through here of some sort. And while this is (in my view) a matter for policy analysis first and foremost, it also requires insight from colleagues about what sort of impact might be achievable, and the resources it would require: full campaign planning will come later, and you won’t be leading on it, but you will probably need a rough idea of the sort of thing it could involve.

Another possible finding at this or the next stage is that you don’t have enough evidence to make a decision, or to formulate your recommendations fully, so you need to loop back to the earlier “understanding” phase and gather some more. This is an example of how these simple diagrams have their limitations!

Understand the causes of the problem

I’ve split this out specifically because a poor or superficial understanding here can lead you to make poor recommendations in the next stage: either they will be rejected by better-informed decision-makers, or they will be implemented and then not work as you’d hoped. Again, ensure you have input from beneficiaries, and do your analysis with reference to your organisation’s strategy. If you don’t understand the causes of your problem, you won’t be able to do anything other than offer a sticking plaster-type policy solution that mitigates the effects but doesn’t stop them occurring again. Equally, your analysis may suggest that a solution of that sort is a viable campaign ask, while tackling an issue at its root is an order of magnitude more difficult. This is essential insight for the next step.

Develop solutions and recommendations

This is the most obvious “policy” element of the whole thing, but should ideally follow from systematic prior work. You should by now have a full understanding of what you are trying to address, and be able to identify the outcomes you want to achieve. Again, do this with input from your beneficiaries / supporters, with reference to your strategy, and in collaboration with colleagues who will be delivering the campaign. The result should be a set of policy recommendations or solutions that will achieve a desired improvement that you can identify, and which will be the goal of the campaign.

Ongoing policy inputs during the campaign cycle

It is not simply a matter of handing the issue over to colleagues at the end of the policy elements of the cycle and wishing them good luck. While (in anything other than a very small team) it will be campaigns and/or public affairs colleagues who are responsible for delivering the campaign, they will need ongoing policy support in each of the remaining stages of the campaign cycle.

Developing the campaign strategy

The nature of the change you want to achieve will have a major bearing on the strategy for achieving it (“process is your Valentine”). Policy advice will be essential to deciding the form of the campaign, for instance in terms of who the key decision makers are and what sort of approaches to influencing them might succeed.

Planning the campaign, delivering the campaign

There will need to be materials for the campaign: reports, analysis, articles, whatever it may be; you’ll have to produce or contribute to them, so work with colleagues on what they need to be. You will also be able to advise on, and help to create, messaging for all audiences (supporters, decision makers and others). You will be able to advise on whether developments get you closer to your policy goal – knowing when to declare a win is an important campaigning skill!

Conclusions

That’s my attempt at a policy cycle: not as something that stands alone from campaigning, but as an integral part of it. But what have I missed out, put in the wrong place, or overemphasised? And if the campaigning and public affairs elements were also expanded, what would a more detailed campaigning cycle look like? Do you have experience of campaigns that matched this cycle well, or that fell outside it? Let me know in the comments, in the LinkedIn group, on Twitter, or by hitting reply.

Licence

My diagrams are available for re-use under Creative Commons licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. NCVO uses same licence on their current website, which does not currently include the campaign cycle material, and licensing rights for earlier material are unclear; I have proceeded on the basis that the current licence provides an appropriate basis for adapting it. Article text is © Policy for Campaigns.